Mr. Harvey Webster, Director of Wildlife Resources at the Cleveland Museum of Natural History tells us, “Now comes the waiting game and guessing on hatch dates. Peregrine Falcon eggs take 31.5 days of active incubation before pipping and anywhere from 24 to 48 hours from pip to hatch. So the average from onset of incubation to hatch is 33 days. 33 days from the date of appearance of the first egg is April 20 in the late evening. However, active incubation often commences with the appearance of the second egg. So 33 days from March 21st is April 23rd in the morning. Suffice it to say that, if all goes well, sometime around Earth Day we should have a hatch, plus or minus a day. It is a tribute to the dedication of both adults that they can incubate the eggs under such uncomfortably cold, wet, snowy and windy conditions as we have experienced in Cleveland over the past 24 hours”.

Volunteer nest monitor, Mr. Scott Wright, tells us that after each egg appears, “The male will smell his new egg to get its scent.... I once saw a male tasting the egg, opening up his beak and gently touching the egg with his tongue!!”

Here is Ranger smelling the second egg.

After this battle, Ms. Sara Jean Peters, now retired from the Ohio Department of Natural Resources, helped us understand why peregrines battle to the death:

"What happens on the peregrine ledge is real and a way that animals partition their resources. In many situations, we only see the replacement. The adult that leaves may go with minor injuries and turn up elsewhere alive, (as happened in a battle between Clearpath and Zenith in March 1999, but both survived). Often, we don't know whether the displaced bird is killed or not. Perhaps you could investigate other predators and see how many work cooperatively and how many work in nothing bigger than temporary family units.

Many animals AVOID this kind of conflict. For example, male robins and cardinals sing to advertise their territories. Many animals will chase intruders; some will stand face to face and growl, bark, or otherwise vocalize to threaten and warn that the territory they're in is occupied. Animal behavior is fascinating.

By the way, dealing with territorial peregrines can become very complicated..… We faced a similar problem in Akron. "Chesapeake", a female that nested at the Cleveland Clinic in 2000 moved to Akron and displaced "J.P.", the female who nested there for several years. J.P. was injured…… Would it be right to keep J.P. in captivity the rest of her life if she can be released, simply because we know she will probably be involved in a fight when she returns to Akron? Even if we release her far away from Akron, she'll likely find her way back (remember, some peregrines migrate to and from South America each year).

Our job as wildlife biologists is to give animals the best opportunities to live their lives in the wild by making certain they have clean water, pesticide-free food....in short, to be certain they have good habitat. We know some will die from any of many different causes, but we also know that, if the habitat is good, some will live as well."

Ms. Peters also stated: "What has interested some folks is Buckeye's behavior. He sat on the eggs and didn't get involved in the fight. Actually, there were two separate things going on. The first is the incubation behavior. This is driven by hormones that develop through the reproductive cycle. First he courts, then he mates, then he shares incubation duties, then he feeds young. It's difficult for birds to just jump into the cycle without going through the steps. ….. As for the fact that Buckeye didn't get involved........ The intruding bird was a female, much larger than he. In talking with peregrine site managers around the Midwest, it seems that in battles, site defense is generally initiated by the bird of the same sex as the intruder with the mate getting involved only to the extent of joining in the chase at the end of the fight."

To read more about the battle between Zenith and SW, click here.

Our thanks to the Cleveland Museum of Natural History for sponsoring the FalconCams and for the stills.

Photos are courtesy of Scott Wright. They can be used in any non-commercial publication, electronic or print, but please give photo credit.

As you know, Ranger is SW’s new mate this year, replacing Buckeye who had been SW’s mate for 8 nesting seasons. It is likely that the aging Buckeye was killed in battle by Ranger. On this date in 2002, another battle took place over this nesting territory - between SW and the legendary Zenith, who had reigned over this nestsite for 9 years. Zenith was Buckeye’s mate before SW arrived. By 2002, Zenith was getting up in years, and she had the peregrine characteristic of leaving her nestsite unguarded during the winter, probably while she migrated south. The word peregrine means “wanderer” and peregrines have been known to migrate 1,000s of miles from their nest. In late winter/early spring of 2002, SW had moved into Zenith’s nest and had already laid 4 eggs by the time Zenith returned from her winter wanderings. A battle ensued and Zenith was killed by the younger SW.

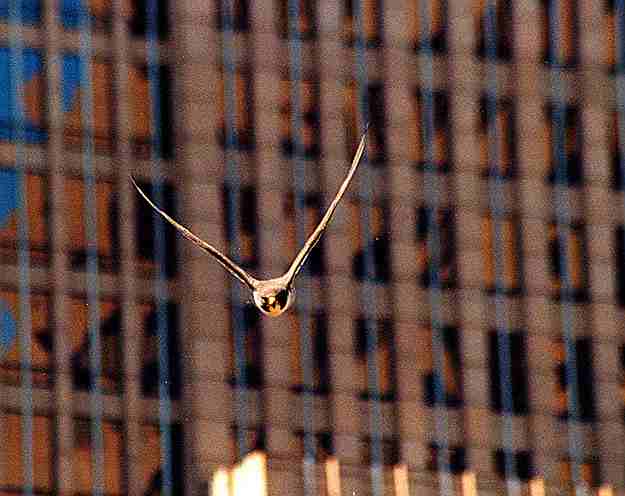

This is Zenith returning to the nestsite…….